The following is a portion from a new travel guide, Texas’ Chisholm Trail, in my American Trails Revisited series (available for the Amazon Kindle and other eBook formats). In the coming months, I will post portions of this guide as I develop it for publication.

Background from Texas-A Guide to the Lone Star State (published in 1940 by the Federal Works Agency, Work Projects Administration, and Texas State Highway Commission):

“The first cattle known to have entered Texas were 500 cows brought by Coronado in 1541. Many of the explorers, fearing a food shortage in an unknown land, brought livestock. Some of these cattle escaped and wandered through the wilderness, to become the nucleus of vast wild herds. The Spanish colonists found a natural pasto, or pasture, covering southwest Texas. Reynosa, in 1757, with a population of 269, had 18,000 head of cattle. De Mezieres (1779) reported that a fat cow was worth only four pesos, yet the ranches flourished. Herds were driven to market in Louisiana by Spanish ranchers in defiance of customs laws. Thus, probably the first smuggling in the State was that of cattle. Owners marked their stock when possible, but most of the cattle were unbranded. The wild herds were not molested by the Indians, who preferred the meat of the buffalo.

It was in east Texas that modern ranching began. James Taylor White, the first real Anglo-American cattleman, established the first ranch of the modern type near Turtle Bayou in Chambers County. Other ranchers followed White to east Texas. They drove their herds to New Orleans to market, using the Old Beef Trail and others. Hides and tallow still had more value than beef. The most important event to pioneer Texas cattlemen was the introduction of Brahma or Zebu cattle from India, a variety scientifically designated as Bos Indicus and differing radically from the European variety of Bos Taurus. It was not until after the Civil War that Brahmas were secured in large numbers. The first record of a successful crossing of these cattle with native stock was in 1874 when Captain Mifflin Kenedy experimented with his herds. Fever ticks had been a barrier to the introduction of Hereford, Shorthorn and other beef breeds in the coastal and southern area. The Brahmas and cattle produced by crossing them with other breeds proved to be immune from tick fever, and were also better beef cattle. As ticks have never been eradicated from some sections, Brahma blood is still essential to the State’s livestock industry.

By 1860, there were more than three million head of cattle in Texas. The Union blockade prevented the shipment of large herds to supply the Confederate army, and at the close of the Civil War the State was overrun with cattle, many of them wild. Longhorns were almost worthless in 1866. Range animals sold for $3 and $4 a head, although in the North butchers were paying from $30 to $40 a head for beeves. Everyone had cattle and nobody had wealth.

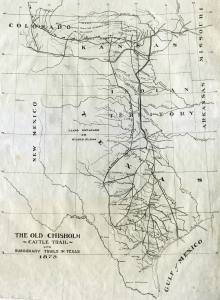

And in Texas, especially in the brush country, wild native stock had flourished. Here the Texas cowboy had emerged. There also were (cowpunchers, from vaca, meaning cow), who were Mexicans. Both of these classes of cowboys had learned to pursue “strays” through the densest thickets. The term “maverick” had come into being as a synonym for unbranded cattle, and there were countless herds of longhorns, too valueless to be branded. Obviously, the thing to do was to drive the herds to shipping points. Yet the nearest railroads were in Kansas and Missouri, 1,000 to 1,500 miles distant.

A few adventurous spirits led the way across those untried miles to the railheads, in the late sixties. Trails, some of them bearing the names of the men who blazed them, came into being, such as the Chisholm Trail. Abilene, Kansas, became a roaring cowtown, followed by Dodge City and other shipping points that sprang up in the wake of the mighty movement of cattle. No other industry in the Southwest had such economic significance or such picturesque aspects. The driving of herds caused towns, customs, and a distinct type of people to grow up beside the trails. About five million Texas cattle were driven to market during the 15 years of trail driving, yet when the railroads reached Texas and the drives were no longer necessary, there were more cattle in the State than when the drives began.”